Local Music Spotlight

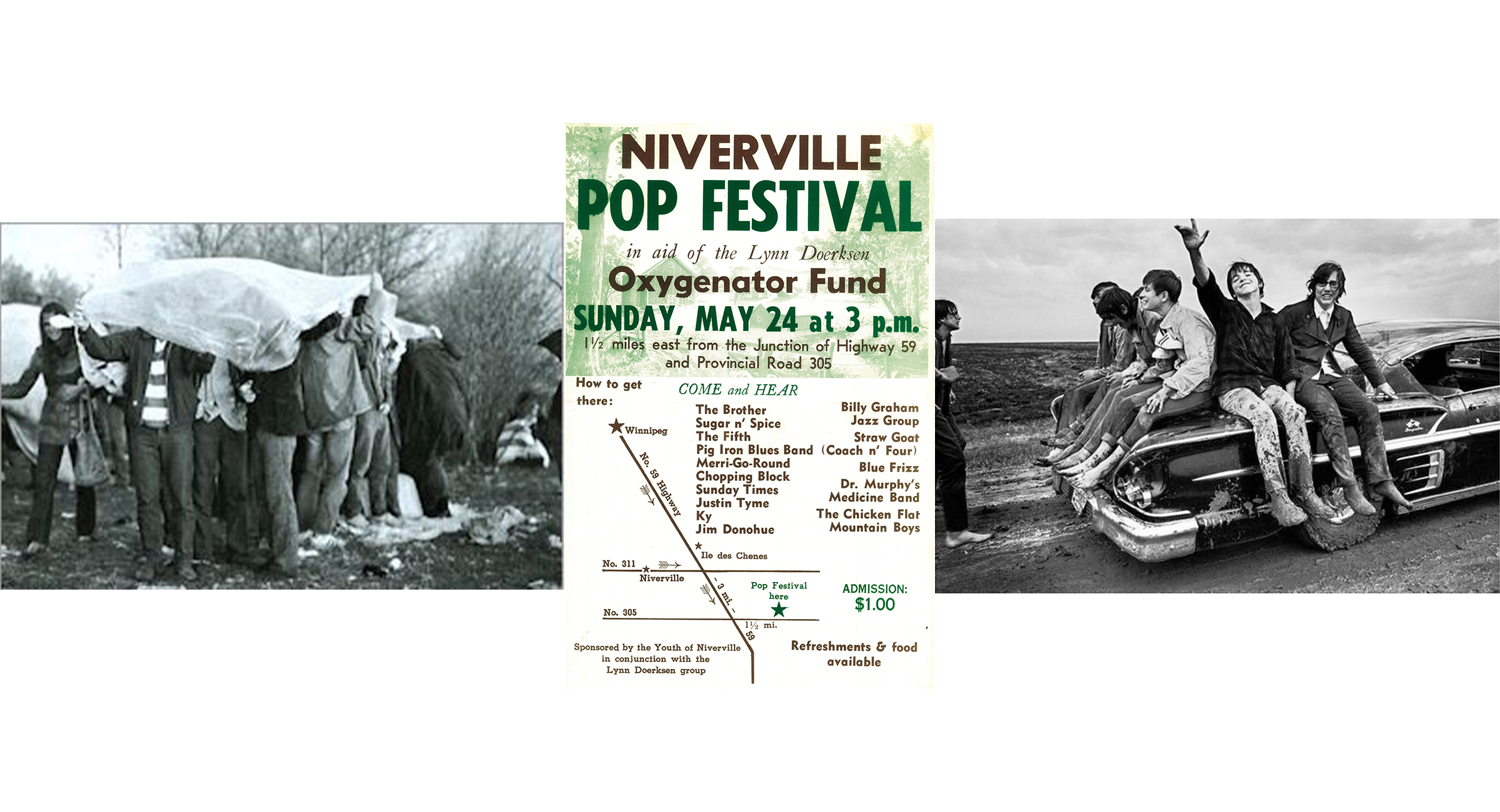

On Sunday, May 24, 1970, 50 years ago this month, Manitoba experienced its very own Woodstock. Billed as the Niverville Pop Festival, the event was staged in a farmer’s field near the quiet rural community of Niverville, 40 km south of Winnipeg. What began as a sun-filled, fun-filled day of music and hippie ambiance, like Woodstock, turned into a mud bath of epic proportions.

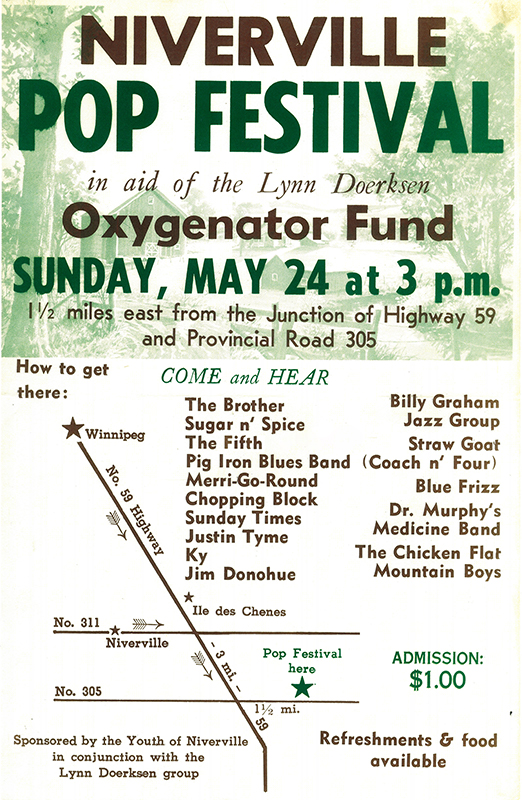

The motivation for the festival came when teenager Lynn Derksen fell off a hayride and suffered a serious injury requiring a $30,000 oxygenator. Efforts to raise funds for the machine had been relatively slow until three Winnipeg musicians, Bill Wallace, Kurt Winter and Vance Masters, collectively called Brother, along with Niverville resident Harold Wiebe, took up the cause. Once word of the charitable event got around, dozens of local bands offered to perform. Niverville farmer Joe Chipilski donated his uncultivated field 10 km from town and parking was arranged on a property across the road. Local merchant Wm. Dyck & Sons provided a 45-foot-long flatbed trailer for the stage. Garnet Amplifiers supplied amplification. Tickets were a bargain at $1 and the show was set to commence at three p.m. on Sunday.

The band The Brother perform onstage.

Organizers anticipated 5,000 attending. By two p.m., double that number had taken over the field, spilling onto adjacent fields and clogging the roads in and out. Again, like Woodstock, many simply abandoned their cars by the road and walked the remainder of the way.

Joey Gregorash kicked things off fittingly with the notorious Fish cheer from Woodstock (“Give me an F…..”). By the time the fifth act, Chopping Block, prepared to take the stage around 5:30 p.m., the sun had been replaced by clouds. What began as a light sprinkle quickly became a torrent of both rain and hail. The Niverville Pop Festival quickly turned into a mud fest as more than five centimeters of rain fell on the site. Surprisingly, the rain failed to dampen the communal euphoria.

The sun-filled, fun-filled day turned into a mud bath.

Vehicles became mired in acres of thick, wet, sticky mud. As local promoter Bruce Rathbone noted, “It took four hours to get four miles through the mud to the highway.” A Winnipeg transit bus had to be towed out of the mud by a farmer’s tractor. “I’ll never forget seeing farmers with their tractors coming to many, many people’s rescue,” recalls Richard Denesiuk, “and pulling cars out of the muddy fields.” Cars that had been parked in ditches now had water up to their windows. Many simply abandoned their vehicles.

Despite initial opposition to a rock festival in his community, a local pastor commandeered a large farm truck and went out to the muddy site. There he loaded the truck with stranded young people and took them all back to his house in Niverville. His wife fed them, helped dry their clothes or got them a change of clothing, and arranged rides for each one back to their homes in Winnipeg. It was a shining moment for the community.

As for me, sporting my girlfriend’s pink raincoat, I spent several hours pushing her little blue Ford through the mud. Spotting my long hair and pink raincoat, three strapping young lads in the car behind jump out and exclaim, “We’ll help you, Miss”. Imagine their surprise when they discovered their Miss was a Mister but, nonetheless, they pushed the car until it was able to get a grip in the mud. I left a pair of shoes stuck in that field. I arrived home late in the evening and went straight into a hot bath.

The event made the front page of both newspapers the following day. It was even the subject of discussion at the provincial legislature when NDP MLA Russ Doern lauded the charitable goal of the event and praised townspeople and local farmers for pitching in when the rain hit. Premier Ed Schreyer suggested that perhaps the festival ought to be called a “Tractor Rock Festival.”

A few days later, festival organizers delivered $8,000 to the head of the Canadian Mennonite Bible College where Derksen attended. Winnipeg General Hospital ultimately purchased an oxygenator in Lynne Derksen’s name.

John Einarson is a local music historian and a CJNU volunteer.