“My dad was a very happy man. He found his own way in life and was able to do exactly what he wanted to do."

I had the pleasure of interviewing Norman Peterson just once – I think it was some time in 1988. Sadly, the popular Manitoba-born and raised woodcarver died of a heart attack a year later at the still young age of 65.

(I still have one of his owls and some of his birds.)

What impressed me about Norman was his approach to art, which was similar to my approach as a freelance journalist. We both strongly believed in producing a finished product that was affordable for all. Rather than looking for the big score, we made our living on sales volume.

“Dad began his career as a woodcarver while we were living in Niagara Falls,” recalls his daughter, Ellen Peterson, who has channeled her own creativity into acting and writing plays.

In the mid-1960s, Norman was working in marketing for an Ontario company called Canada Sandpaper. His idea to increase sales was to market the product to home hobbyists.

The job took him to Niagara Falls where he was upset to find that all the souvenirs were made in Japan. “Dad had been doing some wood carving already,” Ellen recounts, “but now he saw a need to create a product that could compete with the Japanese souvenirs and be affordable.

Norman Peterson was born in 1924, one of 12 children, on the family farm near Narol, just north of Winnipeg. Ellen notes that her father showed an artistic bent from an early age and was encouraged by his mother to pursue his passion. He graduated from the University of Manitoba School of Art and later studied with well-known Manitoba artist Clarence Tillenius.”

One of the keys to Norman’s success, his daughter notes, is that he developed a system whereby he could produce his works of art in an assembly-line fashion. He would line up several “owl” blocks then carve all the eyes one after the other, then the wings, the body.

“He invented the machines he used and the techniques that allowed him to achieve his goals,” Ellen points out. “He was always focused on his work and finding ways to become more productive. I remember he once woke up in the middle of the night with the solution to a problem he was having trouble resolving.”

Norman and his family moved back to Narol after he inherited the family farm. Ellen recalls that he built a new house on the site in 1984 and converted the old farmhouse, dating back to 1939, into his studio.

“Once or twice a year,” she recounted, “he would hold an open house and send out hundreds of invitations. He was planning another one just before he died. He had more than 100 pieces, consisting of a variety of animals in addition to birds and owls, in stock ready to go. For weeks after he died, we had people phoning or coming to the studio asking if we had any pieces to sell.

“Many of his works are in private collections and they are still much in demand online.”

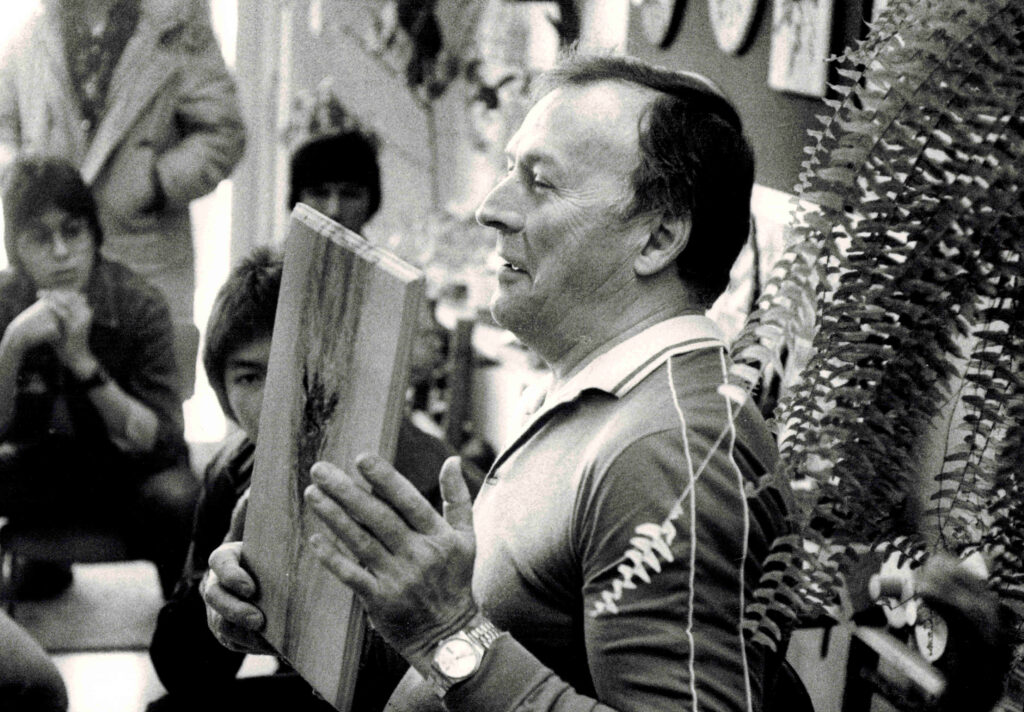

Ellen notes that one of her father’s favourite work-related activities was teaching children the art of woodcraft. “He loved having school groups come to the shop on field trips. He would show them around and teach them no-knife woodcraft.

“My dad was a very happy man,” Ellen Peterson says. “He found his own way in life and was able to do exactly what he wanted to do. Although he could have lived longer, those last five years back here were perfect.

“My dad was my hero.”