Forgotten female heroine of Winnipeg’s early labour movement

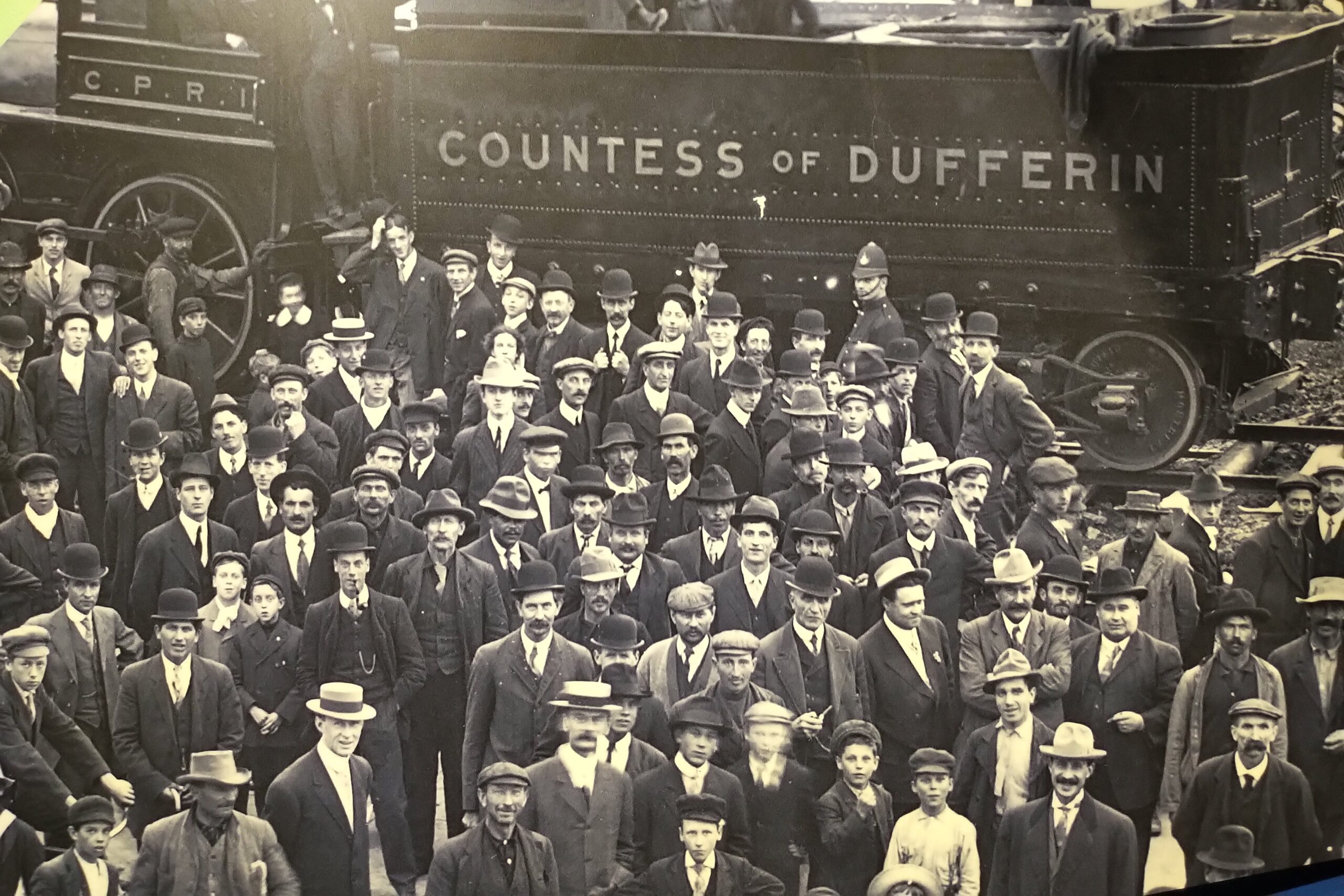

This past month has seen a commemoration of the events surrounding the disruption that accompanied the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919.

World War I had just ended and soldiers who had suffered tremendously for their country came home to find an economy in tatters and the ideas and opinions of another age still prevalent in the minds of those responsible for governance.

Meanwhile new ideas were emerging. Bolshevism was sending intriguing visions of equality and opportunity to a population eager for change. There was bound to be a clash.

Out of this clash of ideas and longing for change emerged the One Big Union. It was a group of trade unionists who were disillusioned with the management of the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada and the influence of the American Federation of Labour. It was dominated by the Socialist Party of Canada. Although it was formed in Calgary, it had its expression of triumph in the Winnipeg General Strike and, while it lost momentum a few years later, it remained in operation until 1956, when the Canadian Labour Congress took its place.

That organization, the CLC, was quite young and vibrant in 1966, when a couple of feisty, young 21-year-olds entered the scene: Brent Naylor and I were brought together by my husband, Glenn, who was then assistant manager of the Construction Labourers Union, Local 101.

Brent was then an itinerant salesman, working for an American by the name of Bob Anderson, himself a war veteran who made a living by selling advertising signage in labour halls and temples across America and later in Canada.

After a couple of years of coming to Winnipeg to sell advertising sign space in the Wall Street Trades Hall, Glenn and Brent stuck up a friendship and convinced me to work part time for Brent, collecting ad copy and cheques. By the time we were both 24, Brent had had enough of working for Anderson and determined to strike out on his own. With Glenn’s help, we convinced the Building Trades Council to allow us to produce a “Buyers’ Guide”, a booklet containing only ads, under their sponsorship. It was a mess, and the following year, I convinced Brent to let me write stories in the publication. This then gave us credentials to approach the Winnipeg Labour Council with a proposal to produce their Labour Annual.

It was in this way that we came to know Mary Jordan. Mary was the secretary to the secretary or general manager of the Winnipeg Labour Council, part of the CLC, but she had also been the secretary to R. B. Russell, the main leader of the Winnipeg General Strike, who ultimately took on the responsibilities for the OBU. Mary was an American, born in St. Thomas, North Dakota in 1899, but growing up here when her family moved to Winnipeg in 1906.

A devout Catholic, Mary went to school at St. Mary’s Academy, just a short walk across the bridge from the family home on Wolseley Avenue on the opposite bank of the Assiniboine. After a brief time working for Eaton’s, she joined the OBU and there she worked until she finally retired in 1972 at the age of 73.

When I met her, she was elderly and conspicuous for her halo of silver hair on top of which perched a “what-not”, a wispy bit of veil, usually in lavender or pale blue, and famous for her 1945 book, Now and Forever, which had been made into a Hollywood movie. She was devoted to R. B. Russell and never married.

We became quite good friends and she told me many stories of the strike and what the mood was like back then. The causes were much more complex than depicted today.

Mary Jordan also told me that when she was researching Now and Forever, published in 1945, she needed to know about the forbidden topic of birth control. She somehow managed to get a package of condoms, which she hid under her pillow when she went to work. Unfortunately, her mother chose that day to change the bed linen and Mary’s little treasure was found. It raised quite uproar in the strict Catholic family.

She wrote several other books, including To Louis, from your sister who loves you, Sara Riel, an historical novel based on letters between Sara, the first Grey Metis nun in Saskatchewan, and her dearly beloved and famous brother. Mary was writing this book when we met. It was published in 1974 and I believe I still have an autographed copy somewhere in my library.

Mary Jordan dedicated her life to the labour movement and to her religion, but she had a sense of fun and was a keen observer of human behaviour. She invited me to her home to celebrate her Bene Merenti Medal (Papal Honour), and here I met many forgotten luminaries of that past age.

Mary Jordan died in 1983.