Dorothy Dobbie

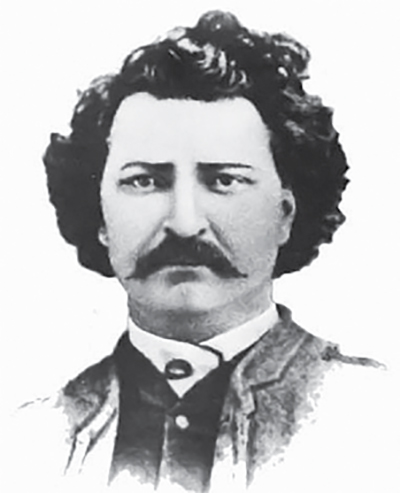

“I know that through the grace of God I am

– Louis Riel, July, 1885, 15 years after

the founder of Manitoba.”

Manitoba entered Confederation.

The year 2020 marks a big milestone in Manitoba’s history. It will be 150 years since Manitoba became the fifth province of Canada.

Most Manitobans do not know their history and while there is not enough room here to tell it well, the Coles notes version follows. How can we properly celebrate what we don’t know or understand?

Today, it is widely acknowledged that without Louis Riel and his determination to protect the Metis way of life, Manitoba’s entry into Canada would have lagged for many years.

Until 1868, the Hudson Bay Company owned the territory known as Rupert’s Land which had been granted by King Charles II, in 1670 to his cousin Prince Rupert of Rhine. This vast area included all of Manitoba, most of Saskatchewan, southern Alberta, southern Nunavut, and northern parts of Ontario and Quebec. The charter included parts of Minnesota, North Dakota and bits of Montana and South Dakota although the Hudson Bay Company’s accepted territory at time ended at the 49th parallel.

In 1867, the same year as Canadian Confederation, the United State purchased Alaska from Russia. This prompted the Prime Minister of the new Dominion of Canada, John A. Macdonald, to enlist the help of Britain in purchasing the territory for Canada. Macdonald was worried that the US would attempt to fulfil its vision of “manifest destiny” and take over the vast northwest.

By the time of the sale of Rupert’s Land to Canada, the Red River Valley had long been the home of the Metis people, the descendants of intermarriage between voyageurs and local Indigenous people who had occupied the area for a couple of hundred years. They hunted buffalo, traded furs and many worked for the North West Company, headquartered in Montreal and competing with the Hudson Bay over the fur trade.

In 1812, the first group of Lord Selkirk’s settlers came to the territory and settled at and near Winnipeg. They would have all died the very first year without the help of Chief Peguis, a Saultaux leader, who rescued them from starvation and cold. Neither the Metis nor the Northwest Company were happy to see the lands settled, disrupting hunting and trading, but the settlers survived and people kept coming. Tensions came to a head in 1816 over the control of pemmican, a vital staple for both the traders and the settlers. Known as the Seven Oak Massacre, 21 settlers, including Governor Semple, were killed.

This was the most famous dispute over the territory but relations between the Metis who were largely engaged in the fur trade and the new farmer settlers continued to be strained over the next 60 years. Yet farms were built on lands that the settlers shared with their Indigenous allies, the signatories to the treaty signed with Lord Selkirk by Chief Peguis and four other chiefs. Peguis and the other chiefs saw the treaty as a way to set out rules for sharing the land. The British and later Canada saw the treaty as providing the newcomers with dominion over the land. This would have repercussions that are still being dealt with today.

The Metis, who by this time had a well-established community which included the first St. Boniface Cathedral built in 1858, understood that their best hope lay in trying to set some terms with Canada. They were concerned about losing of their Catholic religion and their French language and their way of life. In 1869, Riel and the Metis seized Fort Garry and declared their own provisional government to negotiate Manitoba’s entry into confederation to ensure that their rights were protected. This instigated a dispute with some Ontario protestant settlers that resulted in the arrest, trial and execution by firing squad of one Thomas Scott. In spite of this, the Manitoba Act was passed on May 12, 1870, but needless to say, Riel was now a wanted man and even though he was elected to Parliament after confederation in 1870, he was not allowed to take his seat for fear of being arrested. Rumour has it though that he snuck in during the night and did just that, albeit only momentarily.

These years were followed by many broken promises to the Metis and Indigenous people, promises we are still trying to repair today, but the growth of settler population was mercurial. In 1870, our then postage-stamp-sized province held just 12,000 people. Eleven years later, that had swelled to 66,000. Twenty years later, the population exceeded a quarter of a million and by 1911 it was 450,000. Winnipeg was the country’s third largest city.

In spite of our troubled beginning and maybe even because of it, Manitoba has developed a personality that is open to newcomers and still husbands a rebellious spirit of enterprise and ingenuity that has made many contributions to the world.

Our people have excelled in countless fields starting with agriculture, much of our early knowledge gained from our Indigenous population. Manitobans led the way in the development of numerous improved plants to help feed the planet.

Because we were isolated, we had to be ingenious. Old world expertise was applied to many New World industrial needs that saw us pioneering the aviation and even the aerospace industries. Our manufacturing plants fed and clothed the West: we excelled in food production, garment making, equipment and automotive production, printing and publishing, steel and cement making, millwork and stone work, education and innovation and many other pursuits for many years. We produced outstanding medical scientists and doctors. We developed world class artists and renowned performance companies in theatre, dance and music, even making a huge mark on the rock ‘n’ roll world as late as the 1960s.

After a time of stagnation, Manitoba is now ready once again to tackle the world.

This celebratory year of 2020 marks the beginning of the next 150 years and as Premier Pallister so likes to say, “The only thing better than today in Manitoba, is tomorrow in Manitoba!”