"Removing the barriers would do so much more than put people back on the street. The act in itself would symbolize a new beginning where people once again mean more than automobiles."

Dorothy Dobbie

Removing the barriers from Winnipeg’s most famous corner would remove the psychological barriers that have seen us shrink from being Canada’s fourth largest city to its eighth.

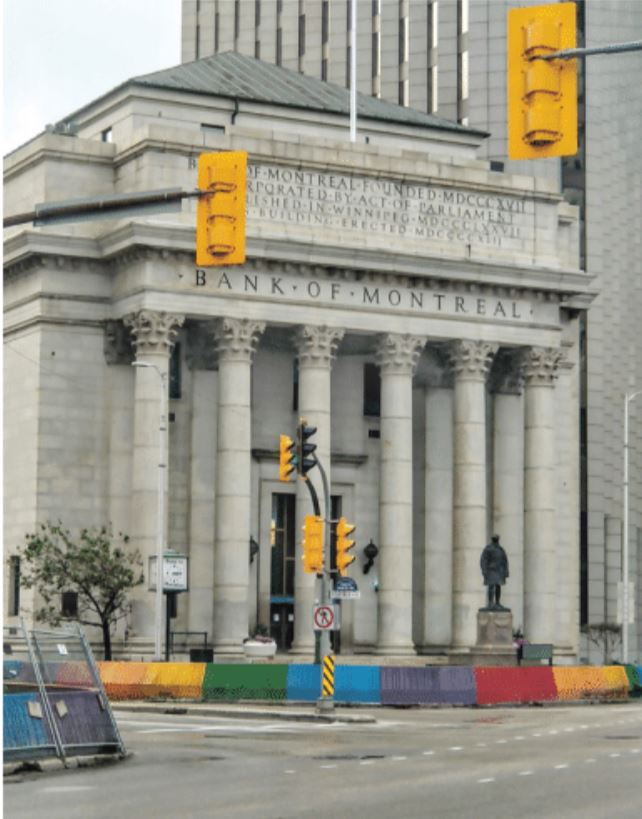

Mayor Brian Bowman promised in 2014 to reintroduce Winnipeg foot traffic to Portage and Main, but here we are in 2023 and those ugly and soul deadening barriers are still in place, now made even uglier with a wash of fading colours. Portage and Main represents the heart of our city.

Now, new and excited ownership of the Bank of Montreal at the southeast corner offers new opportunities for rebirth. Will we take advantage of it?

The heartbeat of our city seemed to slow around the same time the barriers were erected 44 years ago in 1979. Winnipeg’s downtown began to decline. We entered a period of very sluggish, almost non-existent, growth as government manipulation tried to set the path forward: the very expensive deal with Trizec being the first (it is estimated that the enticement offered by the city equalled the total investment by the company), followed by the white elephant that is Portage Place in 1987, which killed three blocks of local free enterprisers who had made shopping downtown a pleasure for a hundred and more years. During that period we fell from being the fourth largest city in Canada to its eighth, just ahead of Hamilton!

Portage and Main has been the scene of countless important community events over the years, from protests such as the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919 to celebrating the end of two World Wars. It is the place where we come together to express our joy. When the Winnipeg Jets won a spot in the playoffs for the first time. Winnipeggers naturally flocked to the city centre, converging on the intersection despite the barricades.

At one time, it was assumed that what is now Broadway would become the main east-west thoroughfare in Winnipeg, but ever since McKenney’s General Store opened at the corner where two ox cart trails intersected, 155 years ago in 1862, the location at the end of the road leading to Portage La Prairie seems to have had a kind of magnetic force that drew traffic to it.

Within a single decade, by 1872, the intersection had become the heart of an emerging town. Another dozen years and the shape of the city to come was already evident with Portage and Main surrounded by substantial and imposing looking buildings.

Over the years, the corner has had many affectionate slings and arrows directed its way. It was labelled the windiest corner in Canada and it was once claimed to be so hot that you could fry an egg on the pavement. There was a postage stamp dedicated to the corner in 1974. Songs have been written about it: Blurt, a British band, has a song called Portage & Main on their Kenny Rogers' Greatest Hit album and Prairie Town by Randy Bachman talks about Portage and Main. There is even a Vancouver rock band named Portage and Main.

Despite all this, and much more, there are those who continue to defend the barriers, claiming that removal would create impossible traffic jams from pedestrians crossing the street. This objection is self-revealing since there are not enough people on the street today to cause any kind of a problem, but the objection proves the point in that, clearly, removing the barriers is seen even by its detractors to be a magnet for pedestrian traffic. Surely that’s a good thing for downtown.

Apparently, according to several news reports, the barrier-supporters tend to be motorists who don’t work downtown. That’s not surprising since anyone who does inhabit that space knows that it’s far quicker to walk half a block to the end of the barriers and dodge traffic to cross the street. Many do this. Going underground can take anywhere from three to six minutes depending on whether you know where you are going or not.

Some worry that returning traffic to the street would hurt the businesses underground. Far from true, since only a few hotel guests and the workers who inhabit the office towers surrounding the underground mall or those who use the indoor walkway go there now, and most will continue to shop there when the street opens. If the concourse had to rely on people from other parts of the city, the shops would go broke very quickly.

Removing the barriers would do so much more than put people back on the street. The act in itself would symbolize a new beginning where people once again mean more than automobiles. It would return to us our natural gathering place, our town square, that no other space can emulate.

Far from stifling business, the opening up of Portage and Main could bring life back to the heart of the city, stimulate new enterprises and just let us psychologically breathe again. We’d still have the option of going underground in winter. But in summer, just think of the possibilities when people return to our most famous corner.

@ 2023 Pegasus Publications Inc.