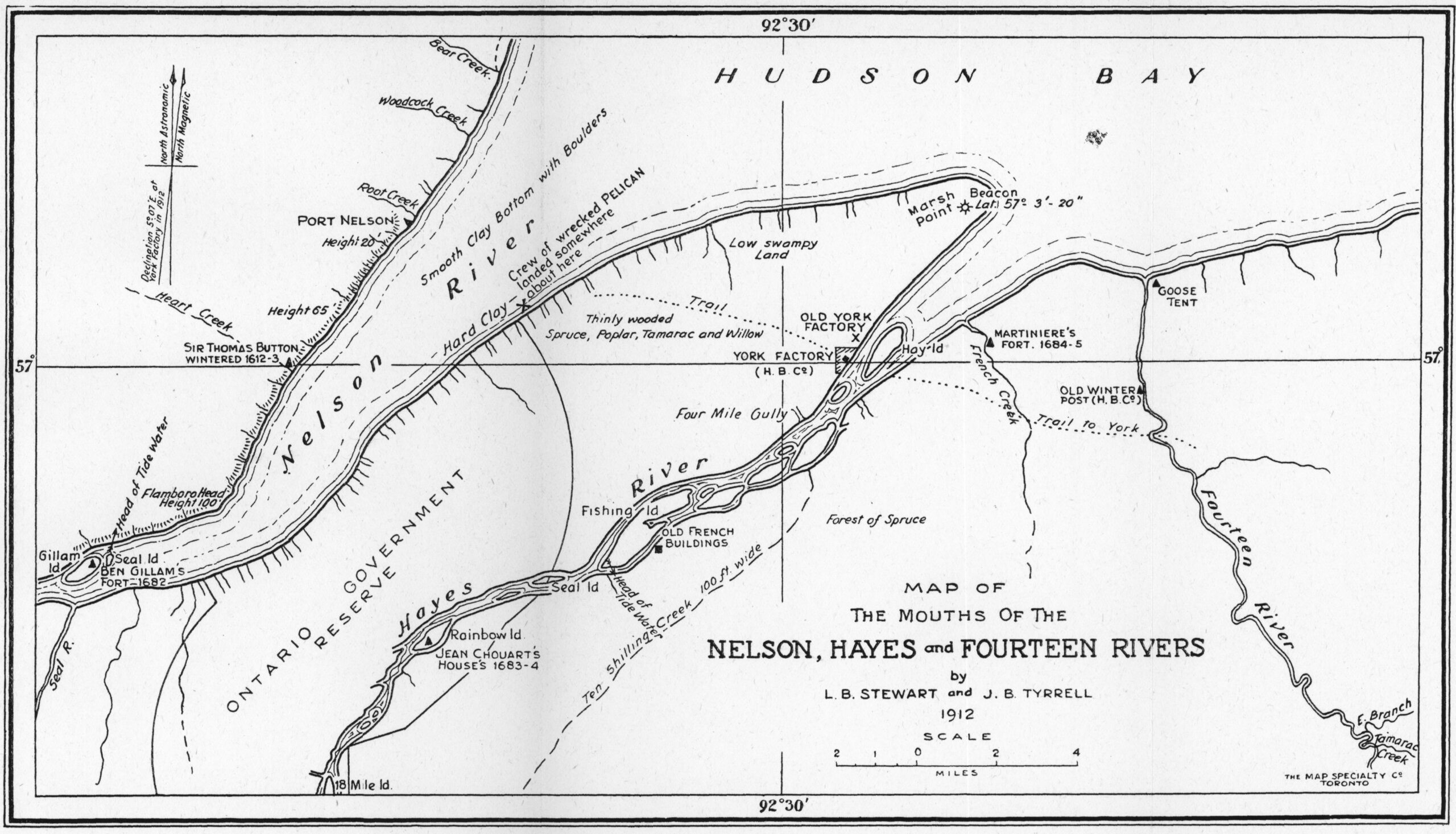

The mouth of the Nelson and Hayes Rivers is where the original trade between first nations and European explorers began in this part of the continent. People have lost or never knew the rich history of First Nations and European contact reaching back to 1611, when Henry Hudson sailed into the Bay over 400 years ago. A year later, Sir Thomas Button sailed in and named the Nelson River, and over the next 60 years, a variety of visitors sailed in and out.

In 1668, Médard Chouart des Groselliers visited the Bay and returned to England with his ship, the Nonsuch, laden with beaver furs. This expedition was so successful that it spawned the establishment of the Hudson Bay Company in 1670.

In 1684, York Factory, a hop, skip and a jump from Fort Nelson at the mouth of the nearby Hayes River, was built establishing the prime fur trading site on the southwestern Hudson Bay for the next 250 years, although many trading posts were established throughout the north throughout that period.

In 1690, Henry Kelsey, who worked for the Hudson Bay company for 40 years, became the first European to see the Canadian Prairies, travelling from York Factory to the interior via the Hayes to the Carrot River and thence to the Assinibioine.

The relationship between the traders, both First Nations and European, was generally mutually beneficial, each partner getting what they wanted or needed from the transactions, but there were times when the contact was unhealthy such as with danger of the transmission of European diseases. Northern First Nations began getting smallpox vaccines as early as 1782, not long after the vaccine was discovered, to prevent decimation of the native traders and destruction of the fur trade.

In the early years, inland travel took place along the mighty rivers that flow north from the west and the south and drain into Hudson Bay.

The mouth of the Nelson and the Hayes rivers has always been a natural inland entry point and it remains so. This part of the Bay is also a natural exit point for goods from the resource-rich prairies to the world.

But what about Churchill?

Meanwhile, things were also opening up at the mouth of the Churchill River, 300 km to the northwest. In 1717 and 1731 respectively, Fort Churchill and Fort Prince of Wales, were constructed in this sheltered natural harbour. Much would happen there. In 1769, for example, the very first Canadian astronomical observations of the aurora borealis took place here. Churchill became an important access point for trade and other endeavours in its own right.

By the 1880s commercial interests had moved from the trade of animal pelts to the export of grain. The feasibility of a railway to a northern port began to be examined. By 1913, after much political wrangling, it was agreed that a rail line north made sense and Port Nelson was chosen as the destination for the terminal because of its shorter distance to tidewater and the better terrain upon which to build the rail bed.

The rail bed was built without fuss, but the port was a different matter. Due to the large amount of silt pouring into the bay, the shoreline was shallow, so it was decided to build an “island” offshore in deeper water and to do this required the construction of a 17-span, steel railway bridge to the island. Both of these constructions still stand as testimony to the ingenuity and hard work of the crews in what grew to a thousand-person town to support the development of the port. But there were other challenges, including a lot of bureaucratic bungling in Ottawa, fierce storms on the bay, and a world war that was sucking up money and men.

After a busy 1917, one year later saw a complete shutdown of the burgeoning town. The plan and all the work were abandoned. It had always been a controversial project, in part due to the fact that it was fiercely rejected by a disappointed Ontario which had wanted this port to be included within their boundaries. Their loss of this territory was not taken lightly.

Several inactive years passed, and it wasn’t until 1925 that the decision was made to move the line to Churchill, despite the unreliable muskeg railbed. The naturally sheltered and somewhat deeper port was held out as the chief reason for the change of plans which now moved ahead with all speed. The first shipment of grain left Churchill in 1929 and the port was completed in 1931.

Sadly, Churchill never lived up to its promise and there were rumours about closure until the second world war gave it new life with the establishment in 1942 of a joint US Canada training base at Fort Churchill five miles away where it continued to support the town until it closed in 1980. During the late 1950s to the early 1960s the population peaked at nearly 7,000.

Today, Churchill is much more acclaimed for its populations of polar bears and curious beluga whales that migrate in the tens of thousands to the mouth of the Churchill River to birth their offspring. The main industry is now eco-tourism, but most of the population, almost 40%, works for the government in administration or health and social services, not counting education.

Today, the permanent population has shrunk to about 870 people serving a trading area of about 3,800.

Perhaps the town should make up its mind to concentrate on the travel trade, pushing belugas, polar bears, and wilderness tours in the summer and northern lights in the winter, sprinkled with historic lore (Fort Prince of Wales) and perhaps overland and sea voyages to wherever the new port ends up being built.

There is a win-win in the NeeStaNan project that expects Churchill to prosper far beyond its wildest dreams of today.